Four Strategies for Human Trafficking Research

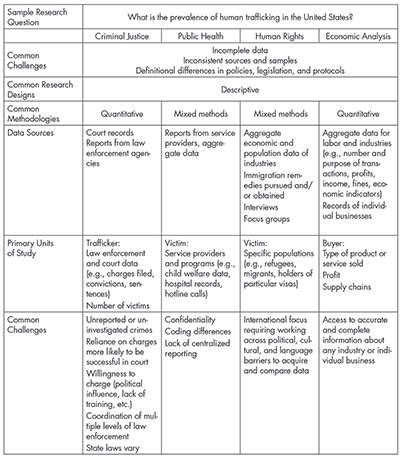

To comprehend and frame an understanding of human trafficking, four distinct but sometimes overlapping strategies are typically used by stakeholders, wittingly or not, to understand its nature and scope: criminal justice, public health, human rights, and economic analysis. Centering research and understanding within one strategy or another is akin to the adage of an individual with knee pain who goes to an orthopedist and is told that surgery is necessary, visits a physical therapist and is recommended a course of exercise and treatments, confers with a yoga instructor and is advised daily stretching.

Practitioners respond with what they know. Any single perspective might be limited in the accuracy of the diagnosis or effectiveness of the suggested remedy.

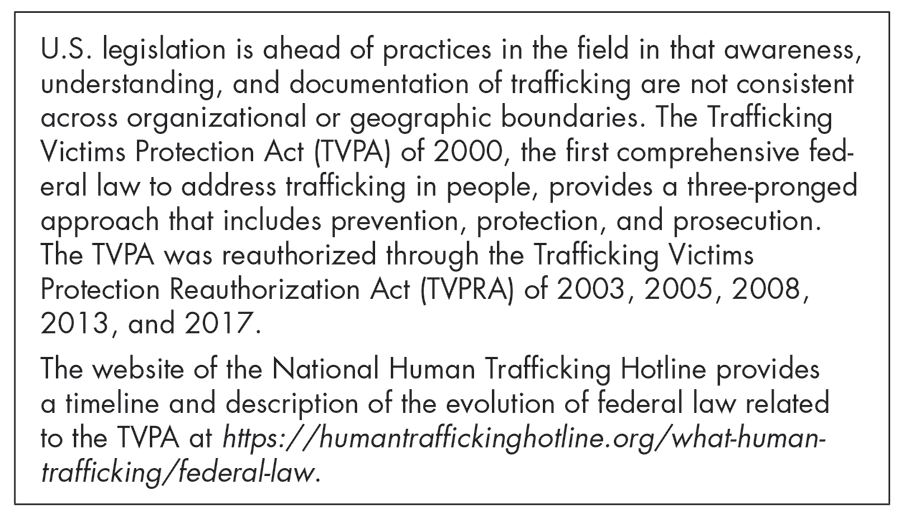

In the United States, research about the phenomenon of human trafficking is growing apace with increased public interest. In the years since the passage of the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA), the first federal legislation on human trafficking (2000), both the general public and investigators have expanded their understanding of human trafficking beyond early notions of a type of sexual or labor exploitation that occurs only in other countries or takes place within U.S. borders among under served and “othered” communities such as immigrants, low-wage earners, or those with substance use disorder (SUD).

Human trafficking is now widely recognized by advocates, law enforcement, and researchers as a complex and multi-faceted phenomenon that merits study. However, the question remains: how best to do so?

Part I: Strategies for and Challenges in Research

Complexities inherent to the phenomenon of human trafficking create challenges for researchers attempting to document and understand the issue. Human trafficking takes on highly variable and sometimes intersectional, multidimensional forms, and traffickers are skilled at adapting to changing threats and opportunities. This diversity and flexibility in the forms and expressions of trafficking make it a difficult phenomenon to identify and examine.

Moreover, as Farrell and de Vries acknowledge, “the lack of clarity in law and policy about the definition of trafficking in persons undermines the efforts to measure the phenomenon because measurement necessitates precision in identifying the objects that are to be counted” (2019, p. 3).

With any research endeavor, the data collected and the conclusions drawn depend on the questions asked, research framework applied, and methodologies used. This introduction to research related to human trafficking discusses both the strategies that might be employed and the data that might be collected and analyzed. Challenges in the four strategies are definitional, methodological, and analytical in nature.

In summary, as the Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons in the U.S. Department of State acknowledged in a September 2023 review of promising practices, “the baseline data on the nature and extent of human trafficking against which to measure future change or program achievements remain largely unavailable” (p. 3). We do not have enough information for a baseline understanding of the prevalence of human trafficking.

Research Challenges Related to the Criminal Justice Strategy

Legal definitions and practices vary from state to state, and from country to country. Even more diversity exists in terms of the understanding and application of legislation from local law enforcement agencies and courts to those at the state or federal level. Research methodology can be organized around specific actions and victim populations defined by law, even though this source of data represents a small slice of the incidence of trafficking.

In the criminal justice framework, the focus is on how the alleged traffickers intersect with law enforcement and the courts. The data is quantitative, including charges filed, civil cases initiated, convictions, sentences, or other court decisions. Data might also be included in reports generated by the various levels of law enforcement and regulatory agencies. To a lesser degree, data might be collected about the number and demographic information of the victims.

Within this framework, no information is available about the crimes not reported, discounted as unfounded, not investigated, or otherwise deemed inadequate to be charged or prosecuted. Human trafficking investigations are laborious and time-consuming, and the relative newness of the crime as identified under federal and state legislation in the United States means that law enforcement officers are still growing their awareness of indicators, evidence, investigative strategies, and potential charges.

Rates of reporting to law enforcement are believed to be low and not fully indicative of actual rates of human trafficking among and within populations. Victims may choose not to report for many reasons that are individual, systemic, and/or conceptual. Barriers to reporting at the individual level may include previous interactions with law enforcement or the criminal justice system that led to mistrust, such as previous arrests while being victimized; cultural and historical distrust of law enforcement; and fear; intimidation, or barriers to testifying or cooperating with an investigation that might be intergenerational, cultural, and historical.

Human trafficking victims experience trauma, the effects of which may be long-enduring, and might conflict with the system’s need for testimony and documentation of detailed elements of the purported crime.

Systemic barriers include criminal justice systems that are under-capacity, do not operate in a victim-centered and trauma-informed manner, and remove all agency from victims and survivors, thereby replicating the power dynamic between trafficker and victim. Investigations and trials are time-consuming and on public record. Victims can be seen as a means to an end: conviction and sentencing of the trafficker.

Victims (the term commonly used for those still in an active trafficking situation) and survivors (those who are no longer being actively trafficked) might never report or might seek advocacy and supportive services while rejecting the involvement of law enforcement. As a result, data collected under such a framework is incomplete, and, while useful, does not provide a comprehensive picture of the phenomenon of human trafficking.

Finally, a conceptual and practical barrier is that victims may not frame their situation and exploitation as human trafficking and might not know they can be reported.

Anecdotal evidence and reports indicate that victims and survivors may first learn of the term “human trafficking” during encounters with law enforcement or service providers. The integrity, significance, and meaning of the term (and, therefore, the crime that it identifies) are often negligible for victims. Victims often do not identify in such a way, and/or while they may recognize that their situation is abusive, they may believe it to be normative or not a crime.

The actual term “human trafficking” is new to the public, and human trafficking victims are members of this broad population. There is a gap between the phenomenon as identified by law and the phenomenon as experienced by the individual. Constructs differ. Given that human beings mediate their experience through language, the felt nature of the experience and the identification and reporting of it will vary accordingly.

Research Challenges Related to the Public Health Strategy

Increasingly, human trafficking in the United States is framed as a public health concern as well as, or distinct from, a criminal concern. That is, the totality of the phenomenon of human trafficking is considered, typically with the person centered, in comparison to the criminal justice perspective centering the trafficker/criminal.

The individual who is trafficked is not viewed primarily as a victim, witness, or means to help law enforcement win a conviction for a crime, but more as a person who has experienced the crime of exploitation and abuse, and who qualifies, due to that exploitation, for services. The agency and well-being of the survivor is the priority.

Prevention, recovery, and long-term outcomes are supported by policy, programming, and funding. Survivors may or may not choose to engage law enforcement under this framework, and the decision to do so is theirs, not that of the service provider, except in two cases: all minors who are suspected to be sex-trafficked and vulnerable and/or disabled adults who are suspected to be sex-trafficked and are covered under mandatory reporting requirements.

Within this framework, the individual and their well-being is centered in actions and decisions, and human trafficking is addressed in a multilevel and intersectional manner. It considers not only individual dynamics and conditions, but also relational, cultural, societal, and structural factors. This contrasts with a criminal justice model, where the focus is victim-trafficker, often with an emphasis on the trafficker. As an alternative, the public health model centers on the victim and survivor, their lived experience, and the service provision that can support and enhance the survivor’s well-being.

Identification and data collection under this framework often center on survivors rather than victims. These survivors may be years removed from active victimization, program reach and service provision, and program efficacy as measured through individuals served and program completion rates.

Service providers in the field of public health are diverse in size, function, and form, focusing on physical, mental, and/or emotional health. The public health field has been innovative in applying research to both inform and adapt professional training and service provision to become better at addressing sex and labor trafficking.

Research in this framework can be qualitative or quantitative, focusing on service providers (professional preparation), service provision (screening tools and documentation), or service recipients (identification and intervention). The data sources might be primary or secondary, individual, or aggregate.

Fundamental challenges relate to how the data is collected, coded, or shared. The protection of confidential health information inhibits sharing critical data. Different service providers might code risk factors or diagnoses in various ways, inhibiting the comparison or combination of diverse data sources. The lack of centralized reporting or data clearinghouses also blocks research.

Researchers can rely on aggregate data sources, such as child welfare data collected at the state level. Service providers outside of medical settings can provide de-identified data related to hotline calls, shelter provided, and the like. Some researchers seek qualitative data from both victims/survivors and service providers.

The unit of study can be the service provided, individuals providing the service, or service recipient. The focus of study can relate to any phase of trafficking—grooming, initiation, exploitation, or intervention—as well as preventive efforts to build awareness.

Research Challenges Related to the Human Rights Framework

The inherent dignity, integrity, and agency of the human being is central to a human rights approach. Human trafficking violates and negates the humanity of a person and exploits the individual as a thing or commodity for the benefit of the trafficker. Under this model, human trafficking is not only considered a crime and a threat to the well-being of individuals, groups, and societies, as in the criminal justice and public health models, but is regarded as foundational, or a priori to both.

The unit of study is a particular population, such as people who hold H2A visas. Research design can be qualitative or quantitative, using primary or secondary data sources. The human rights framework frequently has an international focus.

In the United States, aggregate data sources related to people from other countries are available through federal governmental functions that address immigration processes, such as issuing, monitoring, revoking visas, or requests for asylum, etc. Oversight agencies like the U.S. Department of Labor hold critical data related to the workforce, fines for employers, banned farm labor contractors, and the like.

Trafficking also supports organized crime that can threaten the security of any country. These characteristics motivate some researchers to focus on the global impact of trafficking, studying the movement and treatment of people, products, and money.

Research Challenges Related to the Economic Analysis Strategy

Tracking the number, timing, volume, content, and points of origin or culmination of transactions can contribute to measuring the prevalence of trafficking. If human trafficking were not a lucrative enterprise, traffickers would not be motivated to engage in it. All estimates of the financial benefits that traffickers generate through exploitation of others are simply that: projections of likely revenue.

Research related to sex and labor trafficking generally focuses on a particular business model (the illicit massage industry, migrant farmworkers, online escort services, etc.). Typically, little data is available to define the size of those endeavors: number of people exploited, number of buyers involved, or amount of money exchanged. Any records kept by individual traffickers are not easily accessed by academic researchers, even when investigations are conducted and charges filed against the trafficker.

Within any specific business model of trafficking chosen for research, forensic accounting can track the flow of money. Some business models rely on social media for recruitment of victims and advertising to buyers, thereby providing another avenue for estimating the size of the industry. Qualitative interviews with victims, witnesses, buyers, or others involved with the endeavor can also yield descriptive data that informs financial estimates.

Part II: Potential Focal Areas of Trafficking

Human trafficking is complex and ever-evolving. Data sources are fragmented, incomplete, and often difficult to access or generate. Finding a specific focus in the multifaceted problems that comprise all the forms of trafficking can be challenging. Elements of law, dynamics of abuse, and types of vulnerable populations provide examples of how a research focus can be developed.

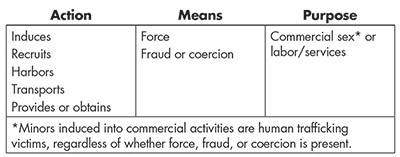

The TVPA was the first comprehensive federal law in the United States to address trafficking in people. The federal definition of human trafficking, as defined by the TVPA, is the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, and/or obtaining of a person for:

- • Labor or services, through force, fraud, or coercion, for the purpose of involuntary servitude, peonage, debt bondage, or slavery

- • Commercial sex act(s) through force, fraud, or coercion

- • Any commercial sex act if the person is under 18 years of age, regardless of whether any form of force, fraud, or coercion is involved

Under this law, any minor engaged in any kind of commercial sexual activity is considered a victim of sex trafficking, regardless of the circumstances involving third-party participation, emancipation status, or age of others connected with the exchange of sex for something of benefit.

Example 1: The Action-Means-Purpose Model

In evaluating a situation to assess whether trafficking has happened, investigators use the Action-Means-Purpose (AMP) Model.

The crime occurs when a perpetrator takes any of the listed ACTIONS, then employs the MEANS of force, fraud, or coercion for the PURPOSE of compelling the victim to provide sex or labor for the profit.

One or more elements of the AMP model can orient research design around particular activities of traffickers.

Example 2: Force, fraud, or coercion

Drilling down into strategies of control through force, fraud, or coercion is an option for research design.

The Polaris Project adapted the Domestic Abuse Intervention Project’s Duluth Model Power and Control Wheel, to demonstrate the types of abuse that can occur in labor and sex trafficking situations. Strategies of force, fraud, or coercion can vary in intensity. Traffickers might start with strategies that are relatively simple and discountable, then move to more intense, isolating, or violent strategies if the victim resists control or tries to leave the situation.

These strategies of oppression and control are employed in a variety of abusive relationships, and the forms of abuse can be intertwined. Here are examples of how traffickers maintain power and control over their victims:

- • Coercion and threats—The trafficker threatens to hurt family members, friends, or pets. If the victim is not a full citizen, the trafficker threatens to call ICE or otherwise initiate deportation.

- • Intimidation—The trafficker moves or vocalizes forcefully, and inflicts harm on the victim’s loved ones.

- • Emotional abuse—The trafficker shames, criticizes, verbally abuses, or manipulates the victim.

- • Isolation—The trafficker keeps the victim in a house or work location, and prohibits any contact with friends or family.

- • Denying, blaming, minimizing—The trafficker accuses the victim of selfishness, lack of gratitude, or unwillingness to uphold contractual obligations.

- • Sexual abuse—The trafficker prostitutes and/or abuses the victims; photographs or films the victim for pornography or online viewing.

- • Physical abuse—The trafficker withholds food or medical care, beats the victim, tattoos the victim to declare ownership, or deprives the victim of fundamental physical needs (food, sleep, access to toilet or medical care, etc.).

- • Using privilege—The trafficker manipulates the victim into providing for the family, controls personal papers, refuses to renew visas, and/or disguises abuse under cover of outward generosity.

- • Economic abuse—The trafficker withholds access to financial resources, does not pay as much as promised or nothing at all, creates debt bondage by charging for rent, food, etc.

- • Reputational harm—The trafficker exerts control by threatening to share visual images, text messages, or other information with family, friends, business associates, or the general public, on social media or otherwise, to shame the victim and create reputational harm.

These forms of power and control can be employed in non-trafficking situations. It is the exchange of sex and/or labor for something of value (money, drugs, rent payment, etc.) that elevates any abuse or neglect charge to that of trafficking.

Research design might seek to illuminate particular forms of force, fraud, or coercion or the ways in which the trafficker adapts the control strategy to the situation or victim population.

Example 3: Environmental conditions exploited by traffickers

Sex and labor trafficking can operate independently of each other or co-exist. These community characteristics are economic, social, and physical conditions that somehow enable traffickers to recruit, market, or transport victims, or connect sex or labor trafficking victims with buyers: tourist destinations, large public events, seasonal farm work, online advertising opportunities, interstate highways, truck stops, highway rest stops, military bases, factories, international borders, and colleges/universities. Any one of these conditions could provide a parameter for designing research methodology.

Example 4: Business models of trafficking

Using data from contacts received by the National Human Trafficking Hotline, the Polaris Project created an important report that identified 25 business models for sex and labor trafficking. (The report does not provide an exhaustive list of all potential forms of trafficking because adaptations are constantly evolving, nor does it imply that all these businesses involve trafficking. Any one of these business models could be the focus of a research project.)

Conclusion

This topic is important and deserves attention. The negative impact of trafficking on its victims is profound and can be overwhelming for anyone seeking to intervene or learn more about its dynamics. All the traffickers need is for any of us to avoid potential frustration or fear and look the other way. Anyone applying the skills and capacity of their intellectual community to addressing human trafficking is appreciated.

Further Reading

Bales, K. 2017. Unlocking the statistics of slavery. CHANCE 30(3):5–12.

Dumont, Michael. 2022. Assessing differences in labor trafficking across the U.S. Unpublished paper. Northeastern University.

Farrell, A., McDevitt, J., and Fahy, S. 2010. Where are all the victims? Understanding the determinants of official identification of human trafficking incidents. Criminology and Public Policy 9:201–233.

Farrell, A., and de Vries, I. 2019. Measuring the nature and prevalence of human trafficking. In J. Winterdyk, J. Jones (eds.). The Palgrave International Handbook of Human Trafficking.

Henderson, Margaret. 2017. Human Trafficking in North Carolina: Strategies for local government officials. Public Management Bulletin 24. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina School of Government.

Henderson, Margaret. 2022. Human trafficking by families. Public Management Bulletin 12. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina School of Government.

Henderson, M., and Hagan, N. 2019. Labor trafficking—What local governments need to know. Public Management Bulletin 16. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina School of Government.

Lane, et al. 2021. Federal Human Trafficking Report. Fairfax, VA: Human Trafficking Institute.

National Institute of Justice. 2020. Gaps in Reporting Human Trafficking Incidents Result in Significant Undercounting. nij.ojp.gov.

North Carolina Human Trafficking Commission. 2023. North Carolina Human Trafficking Charges 2017–2021.

U.S. Department of Justice Office for Victims of Crime Training & Technical Assistance Center and Bureau of Justice Assistance n.d. Human Trafficking Task Force e-Guide. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

Polaris Project. n.d.. Labor Trafficking. National Human Trafficking Hotline. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

Polaris Project. n.d. Analysis of 2020 National Human Trafficking Hotline Data.

Polaris Project. 2023. Analysis of National Human Trafficking Hotline data.

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. n.d. Human Rights Indicators: A guide to measurement and implementation: Summary. Publications Desk. Geneva, Switzerland: Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Senior Policy Operating Group Grantmaking Committee. 2023. Promising Practices: A Review of government–funded anti-trafficking in persons programs.

United States of America. 2000. Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000. Public Law 106-386 (H.R. 3244).

About the Authors

Nancy Hagan, PhD, is a project analyst at the North Carolina Commission on Human Trafficking.

Margaret Henderson, MPA, is a retired teaching associate professor who previously worked for the School of Government of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.