Maryland Rent Courts Fail to Protect Human Rights to Due Process and Fair Trials

In recent years, organizations and researchers in a range of fields have supplemented their thinking and communication with a human rights framework. This framework helps tie together work about specific kinds of human rights that were previously framed as public interest, social issues, racial and gender inequality, voting rights, and other specific rights.

Maryland Legal Aid (MLA) was among the first legal services organization in the country to apply a human rights framework to its advocacy. The idea grew out of a needs assessment in 2009 with its clients across the state about the issues that they and their families face every day. The organization found that major concerns included finding affordable housing, earning a living wage, and receiving proper healthcare. These issues can all be framed as human rights under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a statement adopted by the United Nations on December 10, 1948, as well as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, a treaty that was adopted on December 19, 1966, and ratified by the United States in 1992.

The needs assessment revealed that affordable housing was one of the most-pressing needs for low-income Marylanders—a need that, if left unmet, would prevent them from overcoming poverty. The state’s Rent Court was immediately identified as a system that affected housing outcomes for many low-income individuals and families. Rent Courts were heavily used in Maryland, but had not been systematically assessed. A desire for hard numbers to evaluate the effectiveness of the Rent Court system was the genesis of the Rent Court Study.

MLA works on behalf of renters in failure-to-pay-rent (FTPR) cases. For many years, experiences and anecdotes suggested that existing law was not being applied uniformly in Rent Courts throughout Maryland, and Legal Aid staff suspected this was resulting in unjust outcomes.

Since most defendants in Rent Court cases do not have legal representation, Legal Aid was aware that their experiences were not representative of the complete Rent Court system. For example, default judgments are those made in cases where neither the renter nor a renter’s representative is present at the trial. By definition, Legal Aid had no experience with such cases, so the organization asked On-call Scientists, a program of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), for help in evaluating Rental Court procedures.

The coordinator for the On-call Scientists Initiative contacted me. She knew I had several decades of experience in consulting to agencies, public interest NGOs, and university faculty on evaluation methods and statistics. I met with MLA to help them design and implement a study, guide them through challenges in gathering data, draw their sample, and write the SPSS syntax for data cleaning and summarization. The goal was to produce research that could be presented to officials responsible for administering the Maryland state court system, press, and general public. This evaluation, “Human Rights in Maryland’s Rent Courts” (2016), reached the following conclusions.

First and foremost, Rent Court administrators and judges have a duty to design and administer court processes and procedures that ensure just and fair outcomes that meet the requirements of Maryland law. While robust state, federal, and international laws exist to protect the rights of tenants in Rent Court, the findings of Maryland Legal Aid’s Rent Court Study indicate that Rent Courts processes result in incorrect outcomes and that they are not providing adequate due process; are not maintaining and preserving records of FTPR cases; and are not collecting and retaining basic data on FTPR cases.

We focused on a common type of case—failure to pay rent—and assessed the procedures and outcomes in such cases. The study found that failures of due process were pervasive and occurred at high rates across all districts.

Alarmingly, outcomes at odds with Maryland law were also common. In fact, an estimated 172,635 out of 614,735 FTPR cases in 2012 had at least one error. That is, 28%, or almost three out of every 10, of the cases heard by the courts had either procedural problems or an unfair verdict.

The study demonstrated empirically what the attorneys suspected: The Maryland Rent Court system is badly broken. Here, we discuss the design of the study and the findings in greater detail. The story of the Maryland Rent Courts evaluation shows how the application of quantitative methods can supplement the important gut sense of practitioners working in civil rights and related fields.

Why Does Rent Court Matter?

Due to the myriad and significant consequences associated with an eviction, state, federal, and international law provide important protections for tenants, including security of tenure, the right to due process, and the right to a fair trial.

The right to due process involves proper notice before a case is heard and decided against a party in courts, a meaningful opportunity to be heard in the courts, and an opportunity to appeal a trial court’s ruling. The right to a fair trial incorporates the principles of procedural fairness and equality before the courts. The legal concept of security of tenure in housing means that housing cannot be taken away arbitrarily.

The State of Maryland upholds the human right to legal security of tenure by mandating legal processes and court orders that must occur before landlords are permitted to evict residents. Courts are the primary adjudicators of tenants’ rights, and the duty to ensure fair determinations in FTPR cases is delegated to Rent Courts. In this study, we focused on a specific type of case: where a tenant was charged with failure to pay rent.

In 2012, the year studied, Rent Courts throughout Maryland adjudicated about 614,735 failure to pay rent cases. In the same year, about 33.5% of Maryland’s population—approximately 723,780 households—rented homes. These numbers show that Rent Courts are a dominant force in the rental housing landscape.

The pressures and burdens on Rent Court administrators and judges to manage the staggering volume of cases in Rent Court are profound. Even more profound is the impact that adverse decisions in Rent Court can have on the lives of individuals and families who live in rental housing throughout Maryland. For an already-vulnerable or low-income individual or family, eviction can mean a state of high mobility or homelessness, which can result in serious consequences that touch many other areas of a person’s life.

Threatened or actual loss of housing can result in worsened health conditions; increased risk of unemployment; diminished financial credit; and for children, poor educational outcomes. In addition to the effects of these losses on families and individuals, the long-term economic cost to society from these losses is significant.

Previous research indicates that some subpopulations have greater difficulty with obtaining other housing after eviction and remain homeless for longer periods after being evicted. Of the approximately 723,780 rental households in Maryland, 91,722 are low-income and use federal assistance programs. Among this last set of households, 64% of renters are African American and other minorities, and 21% of renters are individuals with disabilities.

Adverse judgments in Rent Court occur disproportionately in these and other already-vulnerable populations, such as victims of domestic violence and people with poor credit. In these populations, even one negative outcome in Rent Court can cause significant—even catastrophic—hardship.

The volume of cases and the high stakes for tenants in Rent Court together pose a tremendous challenge to courts that need to strike the correct balance between achieving judicial efficiency and ensuring fundamental rights to due process and security of tenure. In addition to a high volume of cases, Rent Court faces challenges such as rapid scheduling of hearing dates; abbreviated trials; unequal power dynamics for litigants who do not have attorneys; minimal due process and evidentiary requirements; and the prospect of eviction—a quite final outcome—within weeks of the proceedings.

When the courts fail to strike the correct balance and efficiency takes priority over the protection of fundamental rights, the problems identified by this evaluation happen.

Designing the Study

This was the first scientific evaluation of Rent Court processes in Maryland, and we decided to approach it using the paradigm of program evaluation. Program evaluation, also known as evaluation research or applied social science, looks at the systems and operations of an organization, program, or agency using methods from a broad spectrum of social and behavioral sciences. This evaluation included design, measurement, data quality assurance, and statistical sampling elements.

The goal for the evaluation was to quantify the breadth and scope of some of the recurrent issues and problems that arise in Rent Court. Specifically, we sought to evaluate whether outcomes were occurring that appeared to violate the law, and whether there were violations of required processes.

Maryland Legal Aid’s Rent Court evaluation monitored Rent Court trials retrospectively that occurred in 2012. The evaluation systematically reviewed FTPR cases from Maryland’s 12 judicial districts over the course of a year by sampling cases from all districts. This evaluation was statewide in scope and draws from an achieved random sample of 1,380 FTPR cases from the year 2012. The sample was stratified by the 12 court districts.

We drew an unusually large sample to make the court officials and team attorneys who were not accustomed to statistical processes more comfortable with the results. In addition, while the overwhelming majority of Rent Court cases involve FTPR, the courts hear other kinds of rent-related cases as well. It was impossible to sample only FTPR cases, so the sampling picked up some cases that were outside the population of interest. The large sample assured that even when the out-of-population cases—those that are not FTPR—are omitted, a large achieved sample size remained.

During the design phase, we attempted observation of ongoing trials. The observations informed the final design of the study, although it turned out that direct observation proved to be an impractical way to gather data. Trials lasted only a minute or two. Multiple cases were dealt with simultaneously. Monitors did not have copies of the complaints filed in the cases they were observing, and it was difficult to collect all the necessary information by listening to the court. This experience led to the decision to evaluate the rental court system based on existing records.

An important part of due process is to have adequate records of what occurred. The courts in Maryland have developed forms that ask about elements of due process, and they are supposed to keep audio recordings of case hearings. The paper forms and audio recordings are kept in the 12 districts where the hearings take place. The forms and audio recordings are critical when cases are appealed; they also provided the data needed for evaluation.

To ascertain compliance with statutory safeguards, we needed to collect data from both the FTPR complaint form and from the trial record itself. We decided to sample from the full set of cases adjudicated over the course of a year. This allowed for a thorough, deliberate, and detail-oriented compilation of data from both the FTPR complaint and the corresponding audio recordings. Sampling cases from a full year helped assure that results were not skewed by factors such as the practices of individual judges with temporary assignments to Rent Court. Stratification by district assured geographic representativeness and ability to get rough ideas of situations within districts if that should become of interest.

However, the decision to sample posed its own challenges. The largest obstacle was that there was no readily available sample frame—no centralized master record of all FTPR cases occurring in the state. In addition, there was no uniform case identifier system across districts.

To overcome this challenge, each district provided counts of the numbers of FTPR cases before the court in 2012. All cases are numbered sequentially in each district, and complaint forms are stored sequentially in each district according to that district’s number formatting. For each district, sets of random numbers were created based on the total number of cases each district informed us they had for the year 2012, and the random numbers were used to select case numbers.

In four districts, this process had to be repeated: After the random sample of case identifiers was created and the cases from the random sample were requested from the local districts, it was discovered that the number of cases for 2012 was not accurate. For example, if the district initially stated that it had 100,000 cases in 2012 and MLA requested the 99,765th case to examine, the local district responded that no such case existed. In these instances, the district then provided new counts of the population size from which cases would be drawn.

Team members went to the court districts to copy the completed forms from the selected cases and obtain the audio recordings. Unfortunately, sometimes adequate records were not available for review. In addition to being a challenge for the study, this revealed weaknesses in the availability of data in Rent Courts and the lack of standardized systems across judicial districts.

In conducting this evaluation, MLA followed good scientific practice and adhered to the principles of non-intervention in the judicial process, objectivity, impartiality, and agreement. In this context, non-intervention means that the monitors had no engagement or interaction with the court regarding the merits of an individual case and did not attempt to influence outcomes in cases indirectly through informal channels. Objectivity means impartial reporting of accurate and reliable information regarding the functioning of the justice system. Agreement involves a common understanding with the judiciary that the trial monitoring is a tool designed to enhance the implementation of fair trial standards.

Consistent with these principles, data collectors did not interfere with any of the judicial proceedings studied; existing MLA attorneys, paralegals, and administrative staff did not take part in the data collection; and MLA informed the former and current chief judges of the District Court of the purpose and goals of the evaluation and obtained the court’s agreement.

The agreement between the organization and the District Court established a partnership that was essential to the evaluation. The agreement meant that the judiciary knew how the evaluation was going to be conducted and the judiciary understood the methods to be used. They knew how sampling was to be done, but, of course, had no knowledge of or influence on which cases were sampled. It is often helpful for the entity being evaluated to know that an evaluation will be done from a scientific perspective; that is, objectively and impartially.

Analysis

In Maryland, a landlord who wishes to evict a tenant is required to fill out a complaint form that was developed by the Maryland District Court. Embedded in the one-page FTPR complaint form are requirements from applicable statutes and Maryland case law that are designed to ensure just outcomes. For this evaluation, we considered compliance with requirements on the FTPR complaint form as a strong measure of the level of due process afforded in Rent Courts across Maryland.

Students, recent law school graduates, or master’s program graduates were carefully vetted to serve as monitors to collect copies of the forms and code the data. The data gathering instrument was designed to examine the issues embedded on the FTPR complaint form. They asked additional questions directly about the extent of the judges’ follow-up during trial on issues already outlined on the complaint form.

Before commencing data collection, monitors were trained on the structure and content of the survey instrument and the FTPR complaints. They were also trained on legal standards, laws, and issues that would be observed in the complaints and assessed through the audio recordings.

To assure that the data file accurately reflected the content of the court records, two data coders examined copies of the complaint forms and audio recording. Each coder entered the values for a set of variables independently that reflected the structure of the complaint form. Using SPSS, they compared the files of coded data, flagged differences, and examined the complaint forms again to make a final determination. Since this was not an effort to develop a coding scheme as a tool to be used in the future, intercoder reliability analysis was not needed.

Once the data were coded, several tests were applied to determine whether due process was followed in a case and an unjust outcome occurred. Due to the time and resources required to code files, the evaluation focused on tests regarding default judgments in FTPR cases. (As noted above, default judgments are decisions a court makes in favor of the landlord despite the fact that neither the tenant nor the tenant’s representative is present.)

Each complaint was evaluated to determine whether one of four outcomes occurred:

- (A) The case was decided improperly; that is, the judgment showed lack of due process and therefore was incorrect according to international, national, and Maryland law;

- (B) The case was properly decided;

- (C) Records were unclear, insufficient, or incomplete;

- (D) The test did not apply. An example of a test not applying would be when a test was regarding default judgments, but the case did not have a default judgment. A “B” result indicates a proper decision. The “A” and “C” results are errors, or failures of the system.

The results were condensed to tallies of the four different outcomes. Three additional tallies were created. One was of cases found to be improperly decided on at least one test. A second was of cases that were found to have unclear, insufficient, or incorrect records on at least one test. A third was of cases that had either kind of problematic finding on at least one test. Calculating sampling estimates, sampling errors, and confidence intervals was a separable task.

To be able to concentrate on other aspects of the evaluation, we requested support from Statistics Without Borders. Justin Fisher of Statistics Without Borders calculated point and 95% confidence interval estimates for percentages and expansion estimates of case counts. These results are summarized below. All 95% confidence limits in this article (also known as margins of error) were 3.4 percentage points or smaller.

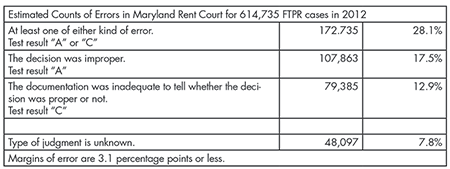

This evaluation found, with a 95% confidence interval of +/- 3.4 percentage points (also known as margin of error), that an estimated 172,635 out of 614,735 FTPR cases in 2012 had at least one error. That is 28% or almost three out of every 10 cases. Table 1 summarizes some of the results.

Particularly alarming is the number of cases in which the analysis showed that the case was wrongly decided against the renter based on existing Maryland law (a Type A error in this study). In an estimated 107,863 out of 614,735 cases (or 17.5% of cases), the study showed that the case was resolved contrary to the law, frequently due to failures in meeting due process and other legal requirements.

Also concerning was the high level of cases for which records were unclear, insufficient, or incomplete. In an estimated 79,385 out of 614,735 cases (or 12.9% of the cases), this type of error was made. In an estimated 48,097 cases (7.8%), even the disposition of the cases could not be conclusively determined. This faulty record-keeping is a failure of due process in itself, given that such records would be essential to an appeal in a Rent Court case.

There also were extensive problems with the audio portion of the case records. In one district, the court was unable to provide the audio recordings associated with cases because it did not record all FTPR cases. In other districts, instead of providing the associated audio recordings for the requested cases, the courts provided recordings of the entire docket. This requires listening to the entire docket to hear an individual case. Additionally, some courts used out-of-date complaint forms that did not contain questions pertaining to current legal requirements.

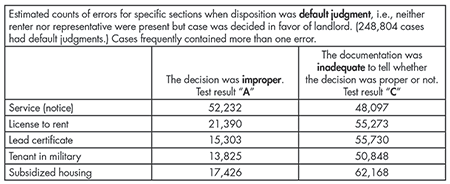

Table 2 shows results for cases for which there was a default judgment; that is, a case where the renter did not appear in court. Note that cases frequently had multiple errors. International law, United States law, Maryland law, and common sense all say that a court should not make a default judgment against a person unless that person has been properly notified about the trial. Nevertheless, in an estimated 52,232 cases, the record shows that this occurred. In addition, in an estimated 48,097 cases, the record was inadequate to determine whether the tenant had been properly served.

The failures in this evaluation were so frequent that mainstream statistical methods were sufficient. Yet, despite the high rates of problems found by this study, it is important to keep in mind that the rates of problems we report here only include a few tests. Since there was such overwhelming evidence that the system has serious flaws, additional assessments were not required. However, we expect more tests would have revealed more problems.

Copies of the original report with details and recommendations were sent to the chief judge of the Maryland Courts and the administrative judge of each court district, and made available to the public at the link below. MLA continues to monitor the situation informally in its day-to-day efforts on behalf of low-income Maryland clients.

This evaluation is an example of the kind of work that can be done when human rights advocates and legal practitioners partner with quantitative researchers. Both the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) and the ASA run programs that help domestic and international rights organizations find volunteer consultants to help design studies and analyze data (see sidebars).

While the issues studied in this analysis had long concerned attorneys, the evaluation provided the first quantitative assessment of the prevalence of problems in the Rent Court system. The study collected objective data on the administration of justice and used it to monitor compliance with the law. This type of evaluation strengthens the right to a fair trial. The information collected and the analysis conducted help to highlight deficiencies in the administration of justice. Fixing these deficiencies would increase adherence to the rule of law and enhance the fairness, effectiveness, and transparency of judicial systems.

Further Reading

Maryland Legal Aid. 2016. Human Rights in Maryland’s Rent Courts (PDF download). (This document contains confidence intervals, legal citations, and other details.)

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (PDF download). 1966.

About the Author

Arthur Kendall is a political psychologist and mathematical statistician. He is an active member of several professional groups focusing on the application of scientific analysis to human rights research, including Statisticians Without Borders, Society for Terrorism Research, ASA Committee on Scientific Freedom and Human Rights, and Science and Human Rights Coalition.